9 May, 2025 • Jordan Elgrably

Poet Mosab Abu Toha Wins Pulitzer Prize for Essays on Gaza

Poet and essayist Mosab Abu Toha who grew up in Gaza under the bombs has won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary.

Tour dates and locations listed at City Lights.

June 2024

Short stories from 25 emerging and established writers of Middle Eastern and North African origins, a unique collection of voices and viewpoints that illuminate life in the global Arab/Muslim world.

"A deeply satisfying collection showcasing an array of brilliant writers who deserve to be better known.

— Lesley Williams. Booklist

“Many in America hold onto broad, centuries-old misunderstandings of Arab and Muslim life and politics that continue to harm, through both policy and rhetoric, a perpetually embattled and endangered region. With luck, these 25 tales by writers of Middle Eastern and North African origin might open hearts and minds alike.” —JHM, The Millions

To order Stories From the Center of the World: New Middle East Fiction, published by City Lights, click here.

Latest articles…

Why We Stay in Beirut, Despite Its Countless Crises

Dec. 3, 2022 | The Markaz Review

Mohamed Al Mufti, "Beirut," collage on canvas, 25x25cm, 2023 (courtesy of the artist).

TMR's editor in chief, Jordan Elgrably, asks four Beirutis why they stay, and how they manage, enduring one crisis after another.

AS WE WERE ALL WATCHING the havoc and devastation being wreaked on Gaza by Israeli warplanes, tanks and troops, and wondering how Palestinians would survive the onslaught to live another day, I asked myself how they managed to live through the conflagrations of 2009, 2014 and 2021. At the same time, a few hours to the north of Gaza, the residents of Beirut are hunkered down, observing the carnage and remembering everything they’ve lived through, including innumerable crises these past few years.

Hope Is Our Last Resort: On Mona Simpson’s Commitment

Los Angeles Review of Books: Jordan Elgrably reviews the seventh novel from the author of Anywhere But Here. July 28, 2023

WHY DO PEOPLE LOS THEIR MINDS, and where do they go when they’re no longer themselves? Is mental illness curable? To the extent that a work of fiction can contend with the enormity of these questions, Commitment, the seventh novel by Mona Simpson, does a masterful job of it. The story sets a family in motion over 400 pages, painting a portrait of a mother, her children, and their friends, in an attempt to get at the heart of what it’s like to have someone in your inner circle completely lose themselves to a mental breakdown.

The Czech-French novelist died on July 11, 2023.

MANY MOONS AGO, WHEN I WAS A YOUNG LITERARY JOURNALIST living in Paris, I happened to meet two American writers at the Café Flore. Their names were William Styron and James Baldwin, and they were at the height of their fame, but Baldwin nevertheless gave me the time of day, and I wound up interviewing him for the International Herald Tribune and then traveling down to Baldwin’s home in Saint Paul de Vence, where I interviewed him for a second time, for the Paris Review. July 12, 2023

David Harper, "Africa People Watching," acrylic on canvas, 91.44 cm x 152.4 cm, 2019 (courtesy David Harper).

Nov. 15, 2022 | The Markaz Review

Jordan Elgrably reads a book about white fear and racism and finds that colorism isn't our only problem.

WE’VE ALL IMAGINED WHAT IT MIGHT BE LIKE to experience an utterly different life, to be someone else — haven’t you ever wondered, for instance, what you would do if you won the lottery and became a millionaire overnight, or how you would deal with losing your home and becoming homeless — if you were to wake up one morning and you were dirt poor, so broke that you were no longer you? Have you not imagined yourself so changed that others wouldn’t recognize you?

“Attack on Salman Rushdie is Shocking Tip of the Iceberg”| Aug. 15, 2022 | The Markaz Review

An attack on one writer anywhere is an attack on freedom of expression everywhere.

Let us be brutally honest with ourselves — Friday’s brazen attack on novelist Salman Rushdie is a threat to freedom of expression everywhere, but it is merely the latest incident in thousands of cases where writers, poets, journalists and filmmakers are censored, imprisoned and even killed. They are hounded as critical thinkers who dissent from the party line, blow the whistle on repressive governments, or because they dare to offend conservative sensibilities.

continue reading

“Palestine in Pieces: “Huda’s Salon”| March 21, 2022 | The Markaz Review

A new film depicts the treachery of being Palestinian living under the Israeli Occupation Forces in Bethlehem.

“There’s Nothing Worse Than War”| Feb. 24, 2022 | The Markaz Review

Letter from the Editor: Russia’s Attack on Ukraine seen from European and Middle Eastern Vantage Points

“The Translator” Brings the Syrian Dilemma to the Big Screen | Feb. 7, 2022 | The Markaz Review

Jordan Elgrably reviews the recent feature film from directors Rana Kazkaz and Anas Khalaf.

Recovering/Remembering Love, Sex and Trauma | Dec. 13, 2021 | The Markaz Review

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi follows her novels "Fra Keeler" and "Call Me Zebra" with a story set in Andalucia.

Kurdish Poet and Writer Meral Şimşek Merits Her Freedom | Oct. 4, 2021 | The Markaz Review

Imagine, if you will, being put on trial for publishing poems and stories extolling the values of human rights and equality — or rotting in prison as you wait to be tried, but being denied books and newspapers for two years, cut off from the world.

Free Speech, Palestinian Stories and the Oscars | Apr. 22, 2021 | The Markaz Review

Despite the increasing diversification of the film industry in liberal Hollywood, the odds are long against writer/director Farah Nabulsi’s The Present winning the Best Short Film Oscar award on Sunday. That’s not because her 24-minute story (now on Netflix) doesn’t pack a powerful wallop, for viewers are confronted with the galling reality of Israel’s military occupation of the West Bank — we watch in anger and disappointment as a humiliated Palestinian father takes his daughter shopping, and has to grovel his way through checkpoints manned by trigger-happy soldiers. Starring the talented Saleh Bakri and child actor Maryam Kanj, The Present deserves an Oscar, but Palestinians have received nods from the Academy before and been snubbed on the big day.

continue reading

Drought and the War in Syria | Jan. 15, 2021 | The Markaz Review

When you live in southern California you become accustomed to, even blasé about catastrophe on a grand scale: wildfires, floods, riots, earthquakes and, often for long stretches, the drought. In a state where droughts have lasted for years, lifetime Californians are occasionally visited by visions of the Apocalypse—particularly during the most recent drought, a seven year chasm from 2011 to 2019. (You can imagine what would happen in a state where nearly 40 million people had to fight each other over water.) I confess that sci-fi movies in which the shortage of water is critical, like Mad Max, 72%, Quantum of Solace and The Book of Eli, affect me more profoundly than horror flicks. The fear of the tap running dry is akin to claustrophobia—running out of water is almost as bad as running out of air, after all. Thus, during the latest drought, I was more than happy to economize my water usage, to the point of flushing every third go and sharing a bath with my wife and young son, depending on who decided to go first.

continue reading

Trump Derangement Syndrome, or How I Learned to Love America: On Ayad Akhtar’s “Homeland Elegies” Nov. 10, 2020 | LA Review of Books

IF YOU’VE ALREADY READ Camus’s The Plague and have been searching for the perfect pre-apocalyptic fiction work to help you navigate our current affairs, this book may be just the provocation. I opened it knowing little about the author, other than having seen him act in the independent feature The War Within and perused his play Disgraced. Neither had prepared me for Homeland Elegies, which turns out to be masterful storytelling for these disturbing times.

Just as a playwright may be tempted to break the fourth wall and talk directly to you in the audience, a novelist wants you to believe that the tales s/he’s weaving are the honest-to-God’s truth — and maybe they are, even if they’re woven whole cloth, because as the ancient Greeks like to shout back at Socrates, “What is truth?” Thespians are first about the performance, always, but one hopes to glean nuggets of vérité, and in this first-person confession about a prize-winning playwright and sometime-actor named Ayad Akhtar, it’s the performance that counts.

continue reading

A Beheading for the Prophet and a Reckoning for France | Oct. 26, 2020 | The Markaz Review

France and its Muslims are at loggerheads over the horrific beheading of schoolteacher Samuel Paty and the national response, which has put Islam on alert.

On October 16 Paty was cornered outside his school in Conflans, a Paris suburb. He was beheaded by an 18-year-old Chechen Muslim who was heeding a fatwa that condemned Paty for displaying satirical cartoons of the Prophet in a class discussing freedom of expression.

A few days later, two women in hijab near the Eiffel Tower were reportedly stabbed by two French women shouting epithets including “dirty Arabs.”

continue reading

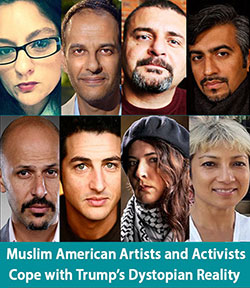

How Are You Feeling? Have the Trump Years Been Good to You? | Oct. 15, 2020 | The Markaz Review

Nearly four years ago, concerned about the state of the nation, we spoke to key figures in the Arab/Muslim American mosaic about what they were experiencing. “Since President Donald J. Trump’s inauguration on January 20th,” TMR noted, “it’s never been harder to be Arab- or Muslim-American. Amidst executive orders targeting Muslims, women’s rights and other issues dear to Democratic values, daily protests and warring words between the Trump camp and opponents have put Muslim Americans in the spotlight.”

continue reading

Two recent books on 20th-century Spain reflect on fascism and forgetting.

Actress Rae Dawn Chong

Will the Harvey Weinstein Scandal Prove to Be a Watershed Moment? Oct. 18, 2017

Why Non-Arabs Should Read Hisham Matar's The Return Aug. 3, 2017

After the Ban, The National, Markaz Review

Feb. 16, 2017

Lakota Sioux "Water Protectors" Inspire the Nation Dec. 1, 2016

On Power, Palestine and Standing Rock, Nov. 24, 2016

Bob Dylan Wins Nobel Prize for Literature? Oct. 18, 2016

"Honky" Raises the Spectre of Racism in Us All

The Markaz Review | July 18, 2016

America has never been more heartbreaking than when it is at war with itself, divided down lines of color, of so-called “race”—the illusion that color or ethnicity really makes us different, whether black, white, Arab, Jew, this, that, “us and them.” DNA tests prove beyond a doubt that we are all more interconnected than anyone could ever guess, so that these seeming divisions can only be perpetuated by fear and stereotypes—indeed, by ignorance. Read more.